My Body Is The House That I Live In, 2019

15mm phosphor coated glass tubing, argon gas, mercury, HT cable, power supplies, bandaids, Arduino modules, Wago connectors, jumper wires, cable, headphones, 2.4” TFT LCD screen, C++ code.

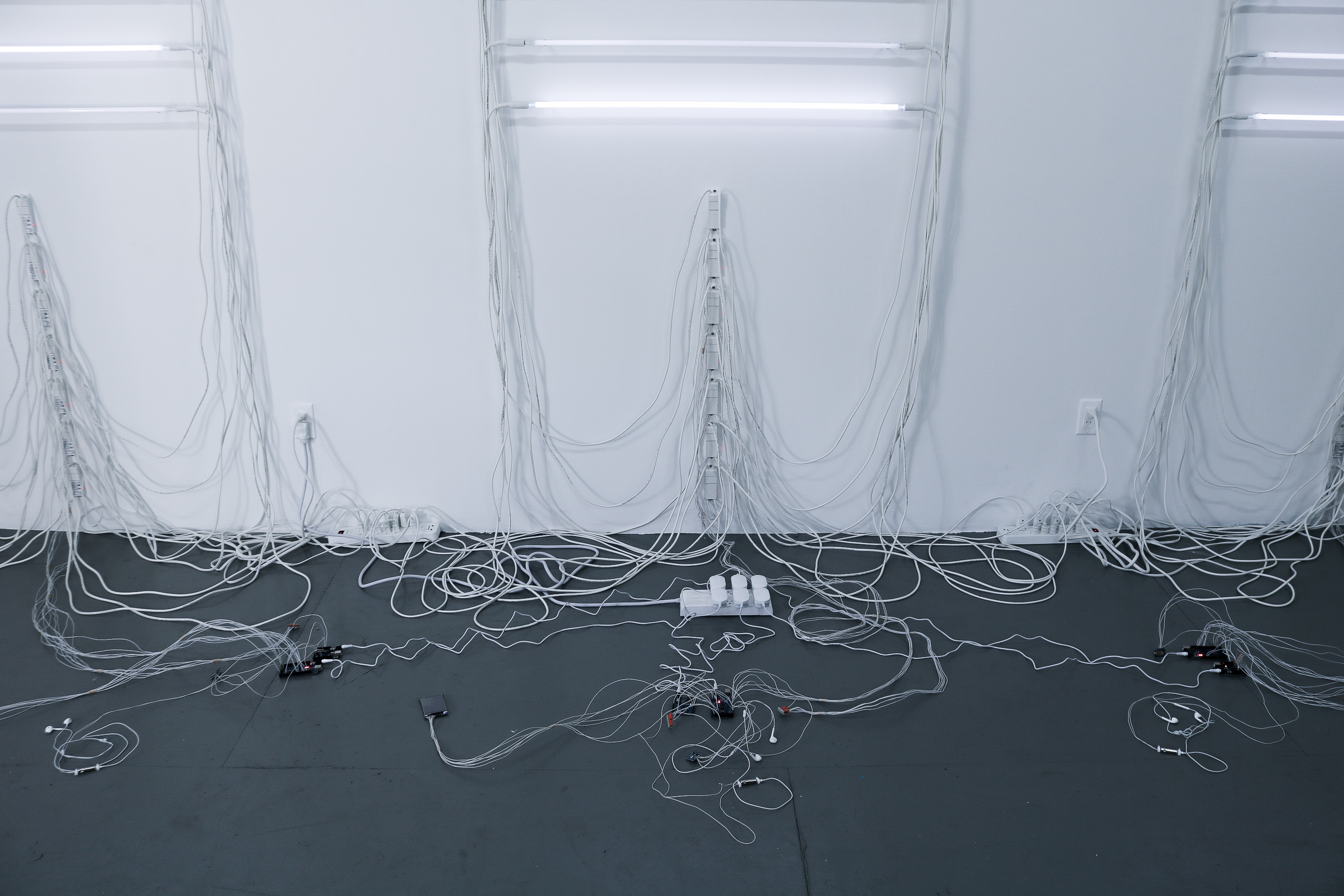

[An industrial space is dimly lit with fluorescent white ceiling lights. The floor is painted gray and the walls are white. On the right facing wall, there are three arrays of seven white neon tubes, each variably lit, with white cords on either end of each tube, plugged into white power strips on the wall. The cords make a rounded “W” shape, with the center of the “W” being a vertical row of power strips mounted to the wall.

[An industrial space is dimly lit with fluorescent white ceiling lights. The floor is painted gray and the walls are white. On the right facing wall, there are three arrays of seven white neon tubes, each variably lit, with white cords on either end of each tube, plugged into white power strips on the wall. The cords make a rounded “W” shape, with the center of the “W” being a vertical row of power strips mounted to the wall. [(Detail) Tangled cords and power strips on the floor beneath a set of white neon tubes. Amongst the cords, there are white earbud headphones, arduino modules and small screens]

[(Detail) Tangled cords and power strips on the floor beneath a set of white neon tubes. Amongst the cords, there are white earbud headphones, arduino modules and small screens]

[(Detail) Close-up of the earbud headphones on the floor. In the blurred background, cords and a power outlet are visible]

[(Detail) Close-up of the earbud headphones on the floor. In the blurred background, cords and a power outlet are visible]

[(Detail) Close-up of the earbud headphones on the floor]

[(Detail) Close-up of the earbud headphones on the floor]

[(Detail) One of the arrays of seven fluorescent tubes, with power strips and earbud headphones beneath. The bottom tube is bright, the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 6th are dim, the 1st and 5th tubes are off]

[(Detail) One of the arrays of seven fluorescent tubes, with power strips and earbud headphones beneath. The bottom tube is bright, the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 6th are dim, the 1st and 5th tubes are off]

[(Detail) Close-up of the powerstrips with cords plugged in]

[(Detail) Close-up of the powerstrips with cords plugged in]

[(Detail) Close-up of the powerstrips with cords plugged in, and the power strip plugged into the wall]

[(Detail) Close-up of the powerstrips with cords plugged in, and the power strip plugged into the wall]

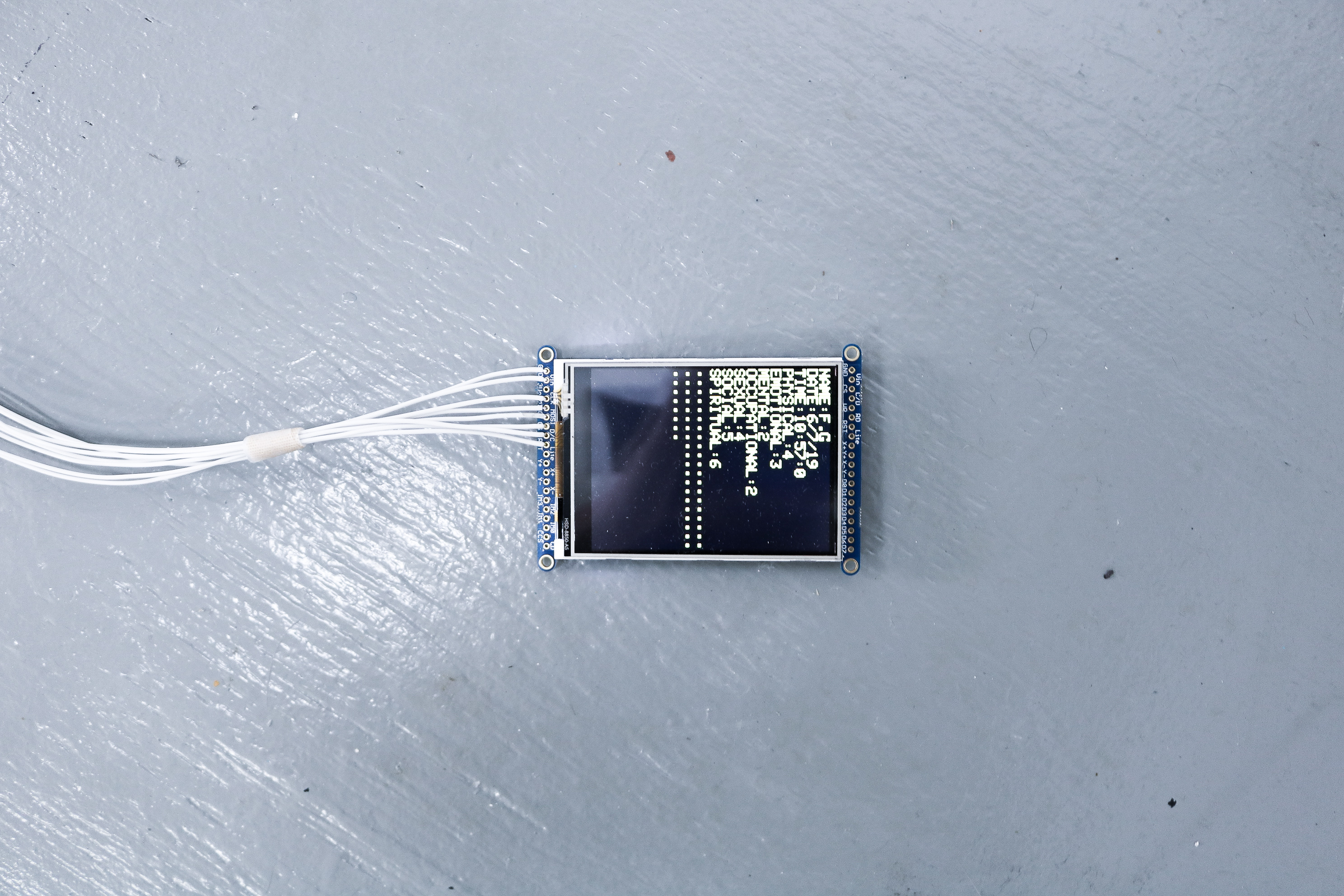

[(Detail) An arduino/C++ module laying on the floor displaying coded data in all upper-case letters. The text reads as follows:

NAME : F. G

[(Detail) An arduino/C++ module laying on the floor displaying coded data in all upper-case letters. The text reads as follows:

NAME : F. G

DATE : 6/7/19

TIME : 18:57:8

PHYSICAL : 4

EMOTIONAL : 3

MENTAL : 2

OCCUPATIONAL : 2

SEXUAL : 4

SOCIAL : 5

SPIRITUAL :4]

[(Detail) Floor shot of tangled cords, powerstrips, arduino modules, and headphones on the grey floor]

[(Detail) Floor shot of tangled cords, powerstrips, arduino modules, and headphones on the grey floor]

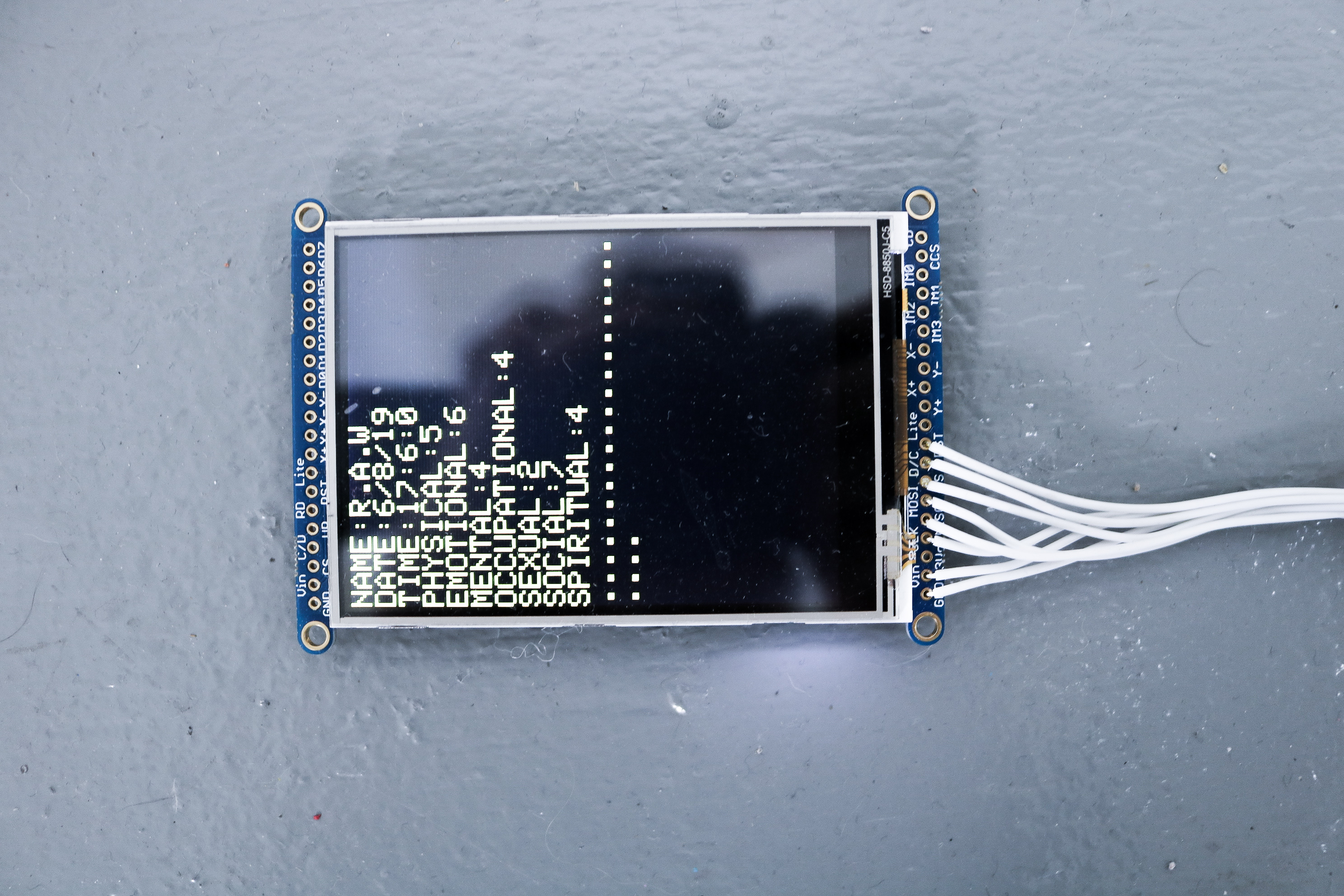

[(Detail) An arduino module laying on the floor displaying coded data of the artist. The text reads as follows:

NAME : R.A.W.

[(Detail) An arduino module laying on the floor displaying coded data of the artist. The text reads as follows:

NAME : R.A.W.

DATE : 6/8/19

TIME : 17:6:0

PHYSICAL : 5

EMOTIONAL : 6

MENTAL : 4

OCCUPATIONAL : 4

SEXUAL : 2

SOCIAL : 7

SPIRITUAL : 4]

The Split Is Vividly Revealed, solo exhibition presented at Nars Foundation, New York, June 2019. All Images: Billy Mason Wood.

The Split Is Vividly Revealed, solo exhibition presented at Nars Foundation, New York, June 2019. All Images: Billy Mason Wood. Neon fabrication: Stephanie Sara Lifshutz.

Installation assistance: Billy Mason Wood and Stephanie Sara Lifshutz.

Please contact romilyalice(@)gmail.com for individual titles/dimensions.

The installations My Body Is The House That I Live In: F.G, L.G and R.A.W, consist of 7 white neon

tubes, placed horizontally, one below the other on the gallery wall. Each tube corresponds to a facet of ‘wellness’:

physical, emotional, mental/intellectual, occupational, sexual, social and spiritual. Every hour, a sick/disabled

participant assigns each wellness category a number from 0-10, 0 being no wellness in that category and 10 being

full wellness; that number will determine each tube’s brightness for the next hour. At 0 the tube will be off, for each

number up to 10 the tube will glow fractionally brighter, with a score of 10 corresponding to full brightness. On the gallery floor, six arduino/C++

modules are coded to repeat the data collected from each participant for the duration of the exhibition.

Computer-generated voices endlessly loop, TFT screens refresh and reload every minute offering the same data

translated into written form.

This work has developed out of a realisation that Western society views pain and sickness as experiences that should be confined to private spaces; as Susan Wendell (2006 p.247)* writes:

One sick or disabled woman/gender nonconforming participant controls each installation for the duration of the exhibition. In this way each work becomes a durational performance of living with sickness, one that views disability as a political issue, moving illness out of isolation and into the public realm.

The work simultaneously points to the inadequacy of our common cultural language surrounding sickness, pain and disability. Making use of the 0-10 pain scale employed by the medical industrial complex, the installations illustrate the failings of representing bodies, pain and sickness in numerical form. Here we see individual experiences reduced to statistics; leaky, messy and multilayered conditions are reduced to numbers on a scale. Whilst the work attempts to bring sickness, chronic illness, pain and disability into the public space, it also reflects upon the pitfalls of trying to make sickness palatable and understandable for a nondisabled audience.

*Wendell, S. (2006). Toward a Feminist Theory of Disability. In: L. Davis, ed., The Disability Studies Reader, 2nd ed. London: Routledge, pp.243-256.

This work has developed out of a realisation that Western society views pain and sickness as experiences that should be confined to private spaces; as Susan Wendell (2006 p.247)* writes:

The public world is the world of strength, the positive (valued) body, performance and production, the able-bodied and youth. Weakness, illness, rest and recovery, pain, death and the negative (de-valued) body are private, generally hidden, and often neglected. Coming into the public world with illness, pain or a de-valued body, we encounter resistance to splitting the two worlds; the split is vividly revealed.

One sick or disabled woman/gender nonconforming participant controls each installation for the duration of the exhibition. In this way each work becomes a durational performance of living with sickness, one that views disability as a political issue, moving illness out of isolation and into the public realm.

The work simultaneously points to the inadequacy of our common cultural language surrounding sickness, pain and disability. Making use of the 0-10 pain scale employed by the medical industrial complex, the installations illustrate the failings of representing bodies, pain and sickness in numerical form. Here we see individual experiences reduced to statistics; leaky, messy and multilayered conditions are reduced to numbers on a scale. Whilst the work attempts to bring sickness, chronic illness, pain and disability into the public space, it also reflects upon the pitfalls of trying to make sickness palatable and understandable for a nondisabled audience.

*Wendell, S. (2006). Toward a Feminist Theory of Disability. In: L. Davis, ed., The Disability Studies Reader, 2nd ed. London: Routledge, pp.243-256.